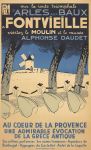

The rather large picture on my bedroom wall to which I awake each morning, a 1935 poster by Leo Lelee, was purchased in two provençal markets: the first, wherein a scruffy facsimile is tied around the trunk of a plane tree in Place General de Gaulle during a Tuesday evening market – or the more romantic sounding marché nocturne – in St Remy de Provence. I’ve acquired souvenirs from this vendor previously over the years and he knows a potential sale when he spots my head bobbing across the jewellery and leather handbag stalls. All the Gallic charm is switched on, hands are shaken in a business rencontre that avoids all that multiple kissing, I’m welcomed back en France, and a price is negotiated. I don’t want the battered copy on the tree trunk merci beaucoup so he promises me another, complete with cardboard transportation tube, by the end of the week. Thus, on Friday, the deal is completed at the second market, this being the morning one at Eygalières: a slightly less cosmopolitan affair, and thereby not as expensive as St Remy but, nonetheless, increasingly affluent, especially with the advent of Hugh Grant’s recent residency into the village environs. Allegedly.

The rather large picture on my bedroom wall to which I awake each morning, a 1935 poster by Leo Lelee, was purchased in two provençal markets: the first, wherein a scruffy facsimile is tied around the trunk of a plane tree in Place General de Gaulle during a Tuesday evening market – or the more romantic sounding marché nocturne – in St Remy de Provence. I’ve acquired souvenirs from this vendor previously over the years and he knows a potential sale when he spots my head bobbing across the jewellery and leather handbag stalls. All the Gallic charm is switched on, hands are shaken in a business rencontre that avoids all that multiple kissing, I’m welcomed back en France, and a price is negotiated. I don’t want the battered copy on the tree trunk merci beaucoup so he promises me another, complete with cardboard transportation tube, by the end of the week. Thus, on Friday, the deal is completed at the second market, this being the morning one at Eygalières: a slightly less cosmopolitan affair, and thereby not as expensive as St Remy but, nonetheless, increasingly affluent, especially with the advent of Hugh Grant’s recent residency into the village environs. Allegedly.

Subsequently, my version of the poster is ensconced in black by a superb framer who lives just down the road from me in deepest Dorset; a craftsman who welcomes my trips to Provence with the same relish as the guy who sells the pictures. They know what I spend my holiday money on once the wine shopping has been accomplished. A black frame suits the lavender-coloured background with its black and white graphics. Of course, you can buy similar on eBay – but they’re not quite the same. I remember once meeting a woman in Arles, who claimed she worked for the estate of Lelee, telling me that it wasn’t possible to purchase the complete poster any longer. In these parts, the heat makes one disinclined to argue a point, especially one which the other side will never admit to losing. Wherever you go in the world, there’s always someone who’s got something that somebody else desires. For example, the sole original Van Gogh on show in Provence is a dull representation of a train, housed at the Musèe Angladon in Avignon. However, being a fan of all things conspiratorial, I don’t believe it’s the only one hanging around in all senses. In those infamous nine week passed at the yellow house in Arles, Vincent sold his paintings before they were even dry for the price of a beer or an hour with a woman of the southern nights. Might not be on public display but it’s difficult to believe none of these masterpieces still exist in the locale. And anyway, my pal in the market is churning them out to order.

Subsequently, my version of the poster is ensconced in black by a superb framer who lives just down the road from me in deepest Dorset; a craftsman who welcomes my trips to Provence with the same relish as the guy who sells the pictures. They know what I spend my holiday money on once the wine shopping has been accomplished. A black frame suits the lavender-coloured background with its black and white graphics. Of course, you can buy similar on eBay – but they’re not quite the same. I remember once meeting a woman in Arles, who claimed she worked for the estate of Lelee, telling me that it wasn’t possible to purchase the complete poster any longer. In these parts, the heat makes one disinclined to argue a point, especially one which the other side will never admit to losing. Wherever you go in the world, there’s always someone who’s got something that somebody else desires. For example, the sole original Van Gogh on show in Provence is a dull representation of a train, housed at the Musèe Angladon in Avignon. However, being a fan of all things conspiratorial, I don’t believe it’s the only one hanging around in all senses. In those infamous nine week passed at the yellow house in Arles, Vincent sold his paintings before they were even dry for the price of a beer or an hour with a woman of the southern nights. Might not be on public display but it’s difficult to believe none of these masterpieces still exist in the locale. And anyway, my pal in the market is churning them out to order.

The poster was a piece of promotional art designed to encourage tourists, having been persuaded that patrimony was now all the rage, to traverse the conveniently emerging ancient sites of Provence; that would be all those antiquities that Johnny Onion Man had been staggering past for eons. In particular, those on the new Grand Tour were advised to visit Fontvieille. This superficially insignificant village, set in the region of what is now the Parc des Alpilles, was the literary home of Alphonse Daudet who wrote a number of seminal pieces about the area that, á la mode Dickens, were published in the capital’s press prior to comprising a small but important book entitled Letters From my Windmill. Daudet wrote his pieces from the contrasting urbanisation of Paris but, like many writers since, contrived to convince the reader that he was, in fact, living elsewhere. And he pulled off this literary trompe l’oeil with exacting veracity. Want to read about rural Provence? Read Daudet.

The poster was a piece of promotional art designed to encourage tourists, having been persuaded that patrimony was now all the rage, to traverse the conveniently emerging ancient sites of Provence; that would be all those antiquities that Johnny Onion Man had been staggering past for eons. In particular, those on the new Grand Tour were advised to visit Fontvieille. This superficially insignificant village, set in the region of what is now the Parc des Alpilles, was the literary home of Alphonse Daudet who wrote a number of seminal pieces about the area that, á la mode Dickens, were published in the capital’s press prior to comprising a small but important book entitled Letters From my Windmill. Daudet wrote his pieces from the contrasting urbanisation of Paris but, like many writers since, contrived to convince the reader that he was, in fact, living elsewhere. And he pulled off this literary trompe l’oeil with exacting veracity. Want to read about rural Provence? Read Daudet.

On the poster, places of potential interest are highlighted under a row of dancing Arlesienne ladies: Daudet’s museum, the aqueducts of Barbegal – always mentioned in the plural but I’ve only ever found one, the underground water systems which are no longer accessible and the shell altar. I must have looked at my framed version for at least a year before actually registering and translating this final piece of information. Shell? Altar? What shell altar? I’d passed many a day in Fontvieille, mostly eating very rare steak at the Bar Tabac but, on one memorable occasion, having purchased an ancient tome from some boot sale or other, traipsing around the village counting wells. I knew the place but had never come across a shell altar.

On a hot (what else?) June morning the Kiwi and I set off in search of the shell. On the road to Arles, fields are ablaze with sunflowers waiting patiently for an artist to pass by. We’ve seen them before – who hasn’t? But they’re like a magnet even for those of us without a handy paintbrush and we spontaneously pull over in order to stand or crouch between the sturdy stems for yet another photo opportunity. Vincent painted twelve pictures of the majestic tournesol – turn to the sun – which we know of. I can understand his lack of ennui.

On a hot (what else?) June morning the Kiwi and I set off in search of the shell. On the road to Arles, fields are ablaze with sunflowers waiting patiently for an artist to pass by. We’ve seen them before – who hasn’t? But they’re like a magnet even for those of us without a handy paintbrush and we spontaneously pull over in order to stand or crouch between the sturdy stems for yet another photo opportunity. Vincent painted twelve pictures of the majestic tournesol – turn to the sun – which we know of. I can understand his lack of ennui.

Nearer to Le Paradou than anywhere else, we spot signage for the Moulin de Coquillage which seems a bit of a clue. This being the premier area in France for olive oil, there are moulins aplenty but not too many boasting a scallop. We take a sudden and startling turn a la droit and make for the mill whereupon we locate and interrogate a pleasant gangly youth. Before we’ve even considered how one might say we’re looking for a large shell in French, the pleasant gangly youth asks whether we’re looking for a large shell and points us in a completely different direction. From this I deduce that hordes of others have travelled this way before without the slightest intention of purchasing olive oil; although, this is simultaneously contradicted by the fact that we’re in the back end of nowhere on a track that looks like nothing more mechanical than a mule has passed by in eons.

Nearer to Le Paradou than anywhere else, we spot signage for the Moulin de Coquillage which seems a bit of a clue. This being the premier area in France for olive oil, there are moulins aplenty but not too many boasting a scallop. We take a sudden and startling turn a la droit and make for the mill whereupon we locate and interrogate a pleasant gangly youth. Before we’ve even considered how one might say we’re looking for a large shell in French, the pleasant gangly youth asks whether we’re looking for a large shell and points us in a completely different direction. From this I deduce that hordes of others have travelled this way before without the slightest intention of purchasing olive oil; although, this is simultaneously contradicted by the fact that we’re in the back end of nowhere on a track that looks like nothing more mechanical than a mule has passed by in eons.

Retracing our route, we come across two provençal types lurking in the trees who look as if they may be the descendants of those who came to the aid of travellers in the 1930s. ‘Looking for the shell’, they ask? ‘Follow the track that says no entry, no cars, entry forbidden and other such welcoming signage’.

On this same holiday, some days later, I once again see my friend in the market who had sold me the original poster. On this occasion, amongst the reproductions of the only time the Tour de France passed through Les Alpilles, I find a small copy of an ancient photo of three Arlesienne ladies, in full traditional dress, posing formally by the shell altar. It seemed such a fortuitous and timely discovery. Monsieur tries to explain the image to me but I stop him in his tracks, saying I’d been there a few days previously. He is horrified and more than a little disbelieving: ‘c’est impossible’, he cries. ‘No-one knows where it is and anyway it’s a private road. One can only go by personal invitation. Well, sorry old bean, but I went, I saw and I took a photo.

Coming back from Les Baux the other day, I recount this story to my daughter and remind her of the photo of the Arlesiennes on my dressing table. From the corner of my eye, I detect a possible spark of interest. The dressing table of one’s mother is often a source of private interests and considerations. Not my mother’s any longer but in another lifetime it was where the remains of delightfully scented powder compacts and carefully used lipsticks rested: things that signified some other part of her. ‘Do you want to go’, I ask, recalling that she’s turned down a trip to the antiquities in St Remy on the basis of having no time for ‘all that Roman stuff’. But something has stirred a sense of adventure. As she’s today’s designated driver, I offer a warning reiteration of the forbidden route she’ll have to traverse. A professional, a parent and a person in her own right, she’s still not developed that nonchalant and perverse ability to ignore ‘prohibited’ that one acquires with age.

Coming back from Les Baux the other day, I recount this story to my daughter and remind her of the photo of the Arlesiennes on my dressing table. From the corner of my eye, I detect a possible spark of interest. The dressing table of one’s mother is often a source of private interests and considerations. Not my mother’s any longer but in another lifetime it was where the remains of delightfully scented powder compacts and carefully used lipsticks rested: things that signified some other part of her. ‘Do you want to go’, I ask, recalling that she’s turned down a trip to the antiquities in St Remy on the basis of having no time for ‘all that Roman stuff’. But something has stirred a sense of adventure. As she’s today’s designated driver, I offer a warning reiteration of the forbidden route she’ll have to traverse. A professional, a parent and a person in her own right, she’s still not developed that nonchalant and perverse ability to ignore ‘prohibited’ that one acquires with age.

She behaves as well as one can hope for; better actually, merely counting and expounding on the number of warning signs. And being driven down this track, as opposed to being in charge of the vehicle, avoiding ruts, roots and potholes, is a totally different experience. On the far right is a wall of stone in front of which a few trees cling perilously to the cliff. From the left, there’s a sudden flash of iridescent blue as unidentifiable bird darts from the trees, across the road to the other side. Is it a blue jay, she asks? I think not – too big and, ironically, too blue. Then another five or six which must have been hiding in the trees in front of the olive mill fly past to join their leader. They are European Rollers, exotic cousins of the jay. On another day, we’ll see single ones perched in solitude on telegraph wires.

She behaves as well as one can hope for; better actually, merely counting and expounding on the number of warning signs. And being driven down this track, as opposed to being in charge of the vehicle, avoiding ruts, roots and potholes, is a totally different experience. On the far right is a wall of stone in front of which a few trees cling perilously to the cliff. From the left, there’s a sudden flash of iridescent blue as unidentifiable bird darts from the trees, across the road to the other side. Is it a blue jay, she asks? I think not – too big and, ironically, too blue. Then another five or six which must have been hiding in the trees in front of the olive mill fly past to join their leader. They are European Rollers, exotic cousins of the jay. On another day, we’ll see single ones perched in solitude on telegraph wires.

Pull in here, I suggest as we reach a suitable piece of gravel off piste, and we abandon the car to walk further down the track into nowhere. It’s the sort of place that, on a good day, there might be large professional guard dogs wandering free in a cheerful but protective provençal attitude; on a bad day, there might be wolves. It would be difficult to hear them coming for here in the Alpilles the noise of the cicadas is deafening. It’s not that pleasant chatter that accompanies other sounds of the South – this is Provence at its wildest. Overgrowth abounds.

Where is it, she demands with more than a hint of angst-ridden urgency? Just behind these trees, I say on reaching the bend. In fact, if you didn’t know where to look you would never see it. And when you do see it, well then you wonder how it can remain so hidden and so unknown to most people. A great and perfectly formed scallop shell is carved meticulously into the rock above a plinth that can only be an altar. She’s as amazed as I was when I first saw this edifice that has quietly contemplated its surroundings for hundreds of years. In the middle ages, it was mistaken for a waymarker of St Jacques on the route that crosses the Alpilles from Italy to Arles and onwards to Santiago Compostela, and many pilgrims somehow found their way along this lonely path. Its history is older and its raison d’être somewhat different as it’s now believed to be a Gallo-Roman taurobolic place of sacrifice.

Wow, she says, that’s weird. And it is.

photos: angladon.com; ebirds.org; monumentum.fr